Animal Monitoring Chronicles (Part 1)

Published:

Low Resource Wildlife Monitoring

With advances in remote sensing technology, there is excitment around new ways to tackle some of the sustainable developing goals. In this project, I focus on goals 2 (addressing food security) and 15 (protect and restore terrestrial ecosystems) while being mindful of goal 13 (combating climate change). Even though my end goal is for use cases in developing countries, this project uses a test bed in a farm in Eastern Washington that had limited access to cellular networks and limited access to power supply. In this blog post, I provide a brief summary of work I was doing in wildlife monitoring on the network edge and a statement of the current direction I am taking in the project.

The Setup

The necessary conditions of interest to me for this project pertain to rugged environments. The main characteristics here are low computational resources (edge devices), limited access to communication networks and electric power constraints. I briefly discuss the location and devices used in the project in line with these constraints.

Devices

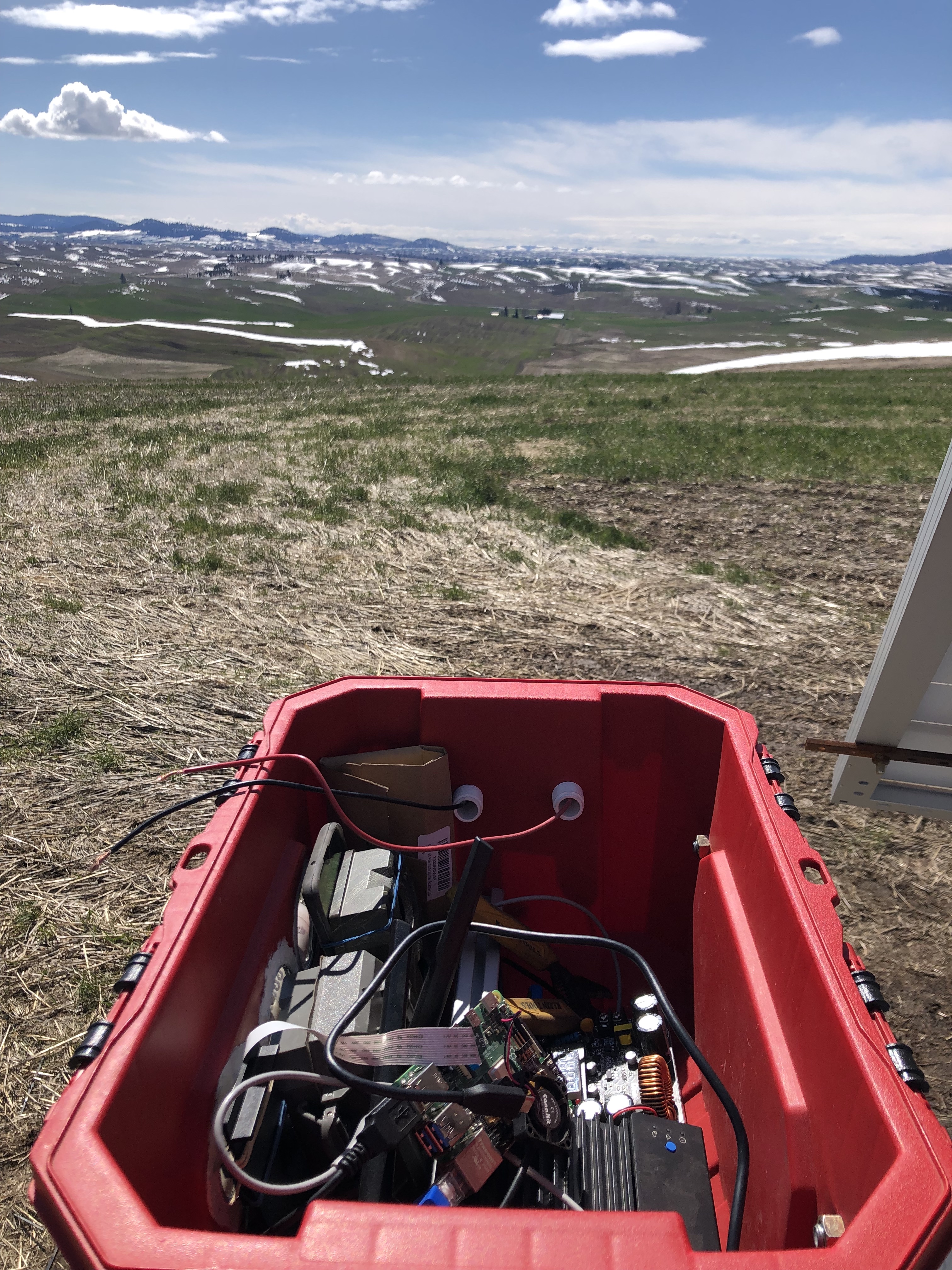

For this project, I started with three edge devices - an android phone, a raspberry pi and a Microsoft Azure Percept. I also had a standard camera trap in the setup to use as a comparison point with a standard device in the environmental monitoring community. The devices would be left out in the field so the setup needed to be water proof. I adapted a home depot bin with cut out view ports and the ports protected by camera lens. There were also holes from the sides to serve as ventilation and passage entrance for wiring. Cameras (phone, rpi camera, camera trap, percept camera) all have to be stable to take pictures/videos through the viewports, which I achieved by utilizing stiff portions of some equipments as support for flimsy ones (eg rubber band around camera trap to support phone).

Due to the breadth of devices, I had to explore with many frameworks in the edge ecosystem (both from this project and from class projects). Some of the noteworthy ones include:

- Android studio with tensorflow lite to setup a system for deploying sample models to an android app.

- ONNX framework for converting between models developed with different ML frameworks (eg between Pytorch and Tensorflow, between pytorch and OpenVINO IR for intel hardware, etc).

- Most of my model experimentation used Pytorch (one of the most popular machine learning frameworks among ML academics)

- Azure Percept Development Kit and other Azure ecosystem services such as Azure IoT Hub, Azure Cognitive Services, Azure ML Studio etc. The custom pytorch model deployment procedure for Azure Percept can be found here.

- Azure blob storage for storing collected data from the devices.

- TVM for further optimizing model runtime for some supported devices (android and rpi)

- The baseline model I started the project with was Tiny YOLOv3. However, the use case cares more about presence so future experiments have been based on MobileNetV2 and EfficientNet-B0 with experiments with novel ML models based on tiny mobile transformers underway and will be discussed in a future blog.

- Most of the project is based on Python and C++ (for working with the Azure percept).

- Docker container provided the on board ML environment for the Azure percept.

- Scheduling of routine tasks such as uploading data from devices to the cloud for experimentation was handled by bash scripting (eg using cron)

- uhubctl came in handy for dealing with usb power status (this was needed to “plug” and “unplug” the camera trap remotely to download data to the rpi

Other notable resources are:

- Google coral for off-loading ML acceleration to a usb stick and works with edge TPU

- Pynq board for experimenting with FPGA acceleration (I used this in a class project for UW CSE 548 with Prof. Michael Taylor. This was a lot of fun experimenting with an open source processor called Black Parrot. A sample setup can be found here)

- Nvidia Jetson provides another set of embedded AI development boards.

- Sabana provides hardware-as-code service (kind of like AWS but for testing hardware as code) founded by Luis Vega who guided me through the hardware ecosystem.

As you can readily tell, the spaces is still young but fast growing! One can easily drown in the heterogenous devices and development frameworks. However, a few mature products are already emerging and (Tensorflow Lite)[https://www.tensorflow.org/lite] is one of them with lots of community backing and quickly supporting more devices. Exchange platforms like ONNX is also instrumental in communicating among the different frameworks.

The location

Eastern Washington has large stretches of land used entirely for farming. Most of these farms are large multi-million dollar farms belonging to few people. Due to this fact, there are few settlements and this area I worked in is technically considered remote. I was mostly working in Farmington, WA, about a 5 hour drive from Seattle. You can drive for over an hour in that region without proper cellular connection and this is worsened during weather events. For instance, I lost connection for about two hours while driving back to Seattle during a snow storm. Again, the farms do not typically have electric power running through them so the only way to access electricity is through batteries and solar power. The farm was testing TV Whitespace technology and so there was a portion of the farm that could access wifi. This allowed remote debugging while in Seattle (using VNC server/client to get around firewall restrictions to the farm network).

Some Challenges

Weather and location access

The farm is setup on a hilly terrain and so it makes sense to have the observation station on top of a hill. During dry seasons (late spring through early fall), it’s decently easy to go up there with a gator. Though I was hesitant to drive it solo at first, given I was a new driver, it was actually fun. However, during the winter, it’s much harder to get up there with the gator so you’d go on foot and it’s a good idea to carry handwarmers and expect lots of snowy mud.

In addition, due to the remote location, getting replacement parts can be a slow process (either because Amazon shipping experiences delays between Spokane - the nearest city - and Farmington, or shops in the area are located far apart so driving around may waste time without results). It does help to call shops to verify availability of products before driving. This situation is echoed by my lab mates who travel to remote places to work on community cellular networks and something to plan for in such projects.

Remote access

The setup was made such that I could perform most tasks remotely. However, when some issues arise that I can’t address remotely, I would have to work with the farm assistant through a video call. This process was definitely more challenging than expected, especially since I would sometimes need him to prod around to figure out why I lost access even though the device is powered on after an incident (eg strong winds blowing down the setup). At times, I would have to schedule another visit to address issues because he could be occupied with other farm tasks for long stretches of time or accessing the setup was not feasible due to weather conditions. At other times, the setup is tested at a part of the farm with no internet or power access. This obviously is even more blinding. Running into these challenges provide helpful insights into deployment challenges to consider for this project and future deployments in developing countries.

Limited community support in a quickly evolving ecosystem

Being at the forefront of the heterogeneous hardware/software ecosystem with fast moving development means you don’t always get to move as quickly as you’re acustomed to developing. Sometimes it takes trial and error, at other times it takes tracking down someone familiar with the device/framework. For instance, following the tutorial for deploying a custom model successfully took much longer than expected, partly due to esoteric issues that didn’t have a lot of community support. I ended up needing to swap model layer definitions to those with system support. Here is a sample error being address a year after I was working with the system. I eventually got the system running with a custom model and capturing the camera output and model prediction to the raspberry pi - the central device.

Hardware and electronics

Additionally, the percept came with an unconventional power specification (19 Volts and 3.42 Amps DC) that took myself and the farmer (who used to work at Microsoft and is active in agrotech) some time to figure out a way to power it in the farm. We settled on a convertor board that provided variable voltage given a fixed 24V suply (from the solar panel). Unfortunately, during one of my hardware debugging sessions, a wire accidentally touched the converter board and shorted it. Afterwards, we were never able to power on the percept 😢. We also could not replace it as the device has been discontinued. The android and rpi were far easier to power on from the solar panel as their wattage were more standard.

Some Lessons

Here, I list a few lessons from the deployment process and will likely serve as a living document as I gather more from the field/remember those I overlooked while writing at this time. If it becomes long, I’ll likely move it to a separate blog.

Breadth of experience doesn’t mean you have to do it alone

This is likely one of the biggest lessons from the deployment process and might resonate more with researchers who have a habit of working in silos. The project opened my eyes to the need to ask for more help than I typically did and I honestly feel a relief adopting this new way of life.

It is easy to try to do everything (especially if you feel you already have some working experience in different areas of computer science). Some CS areas that came in very handy were basic electrical engineering for wiring from a solar panel to devices with different voltage/current ratings, networking skills to debug why TV Whitespace wifi router fails to detect your devices (or the other way around), coding skills to setup remote access and install and debug different software needed to perform image detection on the devices, and a lot of common sense for ploughing through problems you run into. In the end, it wasn’t until I attended a seminar presentation on this paper (see Section 4.2) by another ICTD researcher that I realized how many other engineers/researchers run into the same problems. I now actively find ways to do due diligence in searching for information trove (other experts, blogs, papers, etc) before diving deep to solve issues as a way to move fast.

Managing expectations and reacting quickly

It might be tough to know exactly how different parts of a deployment project will pan out, especially if you want to treat it as a research project. It is extremely easy to get thrown off by minor things like wanting to debug a system remotely and spending time to set up the remote system but still having the setup break (eg by strong winds). Getting the setup running again after such hiccups can also pose extra delays. In such cases, it might be worth it to not only have a copy of the setup at home (this is assuming some distance between the deployment site and development site) but also balance when to rely on the replica and when to face the reality that you can’t replicate all the conditions in the field. Judgement calls on how to make progress so you can focus on the research aspect becomes critical.

Scoping is crucial

In hindsight, the project started with far too many moving parts - too many devices, too many frameworks. It might have been a good idea to quickly assess which of the devices will give the easiest time in setting up a successful system and then progressively add more complicated ones. This is certainly easier said than done, however, if you are in a new domain moving at such a fast pace that, it is difficult to predict where you will have the best success with customizing frameworks to suit your use case. Sometimes, you build this intuition through experience but for sure it still feels like hindsight is 20/20.

Multimodal detection

To situate the work in the ML literature, I am working with some existing datasets on low resource multimodal models for species classification. The motivation here is that audio visual edge devices are common and using both modalities is known to improve downstream tasks such as detecting or classifying fine grained species. This will not only be beneficial for use cases like this edge detection project but can also make such algorithms more accessible to ecologists who might not have a lot of compute resources for their work. More on this part of the work will be discussed in a future blog post. This portion of the project is in conjunction with Prof. Beth Gardner in the ecology lab at UW and is supported by the Computing for the Environment Initiative Award at UW and Microsoft AI for Earth Grant.

Conclusion

Though this project has had a long and windy road, I feel more comfortable in the ecosystem now and have lot of experience under my belt for going through the whole pipeline of developing models and deploying them in the real world. With the full pipeline ready, it’s time to publish some results from different parts of the stack (starting with model development, then to efficient deployment). Afterwards, lessons I learned from my networking classes (especially projects around federated learning) will come in handy as I continue to explore the tradeoffs between edge computing and cloud machine learning.